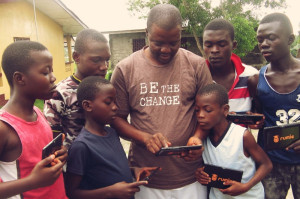

B. Abel Learwellie (center) initiated a neighborhood educational program in the wake of nationwide school closures, following the Ebola outbreak. (Camp for Peace)

Liberian human rights activist B. Abel Learwellie has seen more death and destruction than any person should have to endure. He’s lived through two civil wars, during which he lost family members, witnessed brutal killings, and was kidnapped and forced to serve as a child soldier. Now, he’s on the frontlines of another massacre: the deadliest Ebola outbreak in history.

Yet, through it all, and despite having battled his own personal demons, Learwellie has managed to persevere, finding both hope and relief in the work of helping those in need. I recently had the opportunity to ask him about this work — from his current campaign to combat the spread of Ebola, to his longstanding efforts to build a more peaceful society after over a decade of war.

What have you been doing since the outbreak?

Since the intensification of the outbreak, I launched a campaign called, “Know the Facts About Ebola to Save Yourself and Your Country.” It has been very successful so far and it still continues as more cases are reported and more deaths occur. Liberia alone has lost over 3,000 people as a result of the Ebola outbreak. In my campaign, I educate people on how to take preventive care and follow the advice of health care workers. About 75 percent of Liberia’s population is illiterate, so as part of my campaign, we translate Ebola awareness messages into the various Liberian local languages in order for them to understand and take these preventive actions. I also distribute preventive materials like disinfectants, chlorine, chloral, soap and buckets to various communities. I also do advocacy, referring and connecting sick people to various health teams for ambulances to take them to hospitals, as well as conduct lay counseling to people whose relatives have died from Ebola. Part of my plan right now is to bring together children who have been orphaned as a result of the virus and incorporate them into our educational program after the Ebola crisis. There are instances where an entire family has been wiped out and left with only one or two children, some of whom are now suffering to fetch food and other basic necessities for themselves.

How have you fared during this outbreak on a personal level?

I have lost over 100 people, including close relatives and friends. We live in horrific fear and danger on a daily basis. It has become a routine: You wake up every morning and you hear nothing but the death news of a close friend, relative or a neighbor who has died from Ebola. It is disgusting and troubling. Hence, I had to break the yoke of fear and regain my energies to continue my welfare assistance and join the fight against the invisible enemy of Ebola. I have also been reminded of when I was in the bush as a child soldier, trying to survive. It has, at times, made me feel as though life is very meaningless, especially since I have not seen very much meaningful living. All my life has been struggle — struggle for food as a child before the war, then being captured, beaten and recruited as a child soldier. Now, at age 40, I’m faced with an Ebola outbreak that has taken friends and relatives from me, including my mother. The greatest coping strategy has been helping people, giving them hope, educating them about the deadly virus and giving them preventive materials. I feel strong and hopeful in doing all these things.

What kind of work do you normally do, and were you doing before the outbreak?

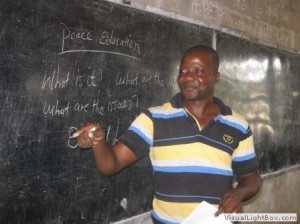

I am a psychosocial worker and a teacher. I work with the Trauma Healing and Reconciliation Program of the Lutheran Church in Liberia as a trainer and a resource person. I have an oversight responsibility to conduct peacebuilding and conflict resolution-related programs, which include violence prevention, campaign training, and advocacy for people isolated and discriminated against because of their association or involvement in the civil war. I also do peace education with schools across Liberia. One of my primary focuses has been working with former child soldiers, helping them to rediscover their lives, build up their self-esteem, giving them hope for the future, and creating a space for them to cultivate their potential and energy.

Building peace in the classroom

In addition to the above basic engagement, I also created an opportunity for Liberian youths — specifically college students studying sociology and other social sciences — to volunteer in a community engagement program, where their young skills and expertise can be utilized. It’s a grassroots community-based organization called Camp for Peace Liberia and it offers support to young people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder by helping them participate in Liberian society.

How did you get into this kind of work?

My motivation came from the inhumane suffering I underwent as a child before, during and after the Liberian civil war. When I was a teenager, I planned to practice medicine as a profession, but this dream eventually died at the onset of the Liberian civil crisis. I was kidnapped in 1990, humiliated and later recruited as a child soldier. I lost several relatives, including my father, and witnessed several catastrophes and massacres as the result of the civil war. My involvement as a child soldier not only killed my vision [to become a doctor], but it also took from me my personal human nature, enslaving my happiness as a young person, and leaving me with both physical and psychological injuries.

At one point, I felt that life in its totality was just meaningless, and thought of committing suicide. But as time went on, I decided to re-commit my entire life to helping people in suffering. I felt this would be one way for me to reduce my own traumatic stress and move on with life. This is how I got to the high point of what I am doing now, helping former child soldiers. I am happy doing this because it has kept me alive and enabled me to continue pressing on.

How does the current crisis compare to the civil wars you’ve witnessed?

This is more intense than the civil war, which lasted for 14 years and took the lives of 250,000 people. Ebola has lasted for just seven months and has killed 3,000 people. What makes it worse, in some respects, is that you don’t see the killer. Moreover, there is no escape, because no country is willing to accept anyone from Liberia as a refugee, as they had during the civil war. It is like being in prison. You can’t ambush Ebola with any physical bullet — it does random killing. So, it is more scary as compared to the civil war.

How do you work for peace in a situation like this one, where the perceived enemy is a virus, and not a dictator, or warring factions?

The best things to do are to educate, spread awareness of the facts and take precautionary measures. My campaign has saved the lives of so many thousands, which I believe is part of the peace we are still seeking. Peace for us now is being safe and kicking Ebola out of Liberia.

What gives you hope right now?

Above all else, trusting and believing that God is able. I know with God all things are possible. Secondly, the many resources I have in my possession. These include the friends both inside and outside of Liberia, including you [reading this], who make me feel that we are not alone. The support of my friends in the United States and Canada, whose resources are helping me to do what I am doing, is greatly giving me the hope and energy I have.

0